Songbird nestlings in the Arctic struggle in cold, wet years, but the changes forecast by climate models may lead to even more challenging conditions, according to new research in The Auk: Ornithological Advances.

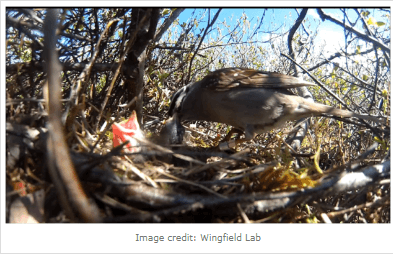

Jonathan Pérez of the University of California, Davis, and his colleagues compared the growth rates of the nestlings of White-crowned Sparrows, which have a broad breeding range, with those of Lapland Longspurs, which are an Arctic breeding specialist. They predicted that nestlings would grow faster in warmer, drier conditions, that clutches laid earlier would do better, and that the nestlings of specialist longspurs would grow faster than the generalist sparrows.

They found that growth rates were higher overall in 2013 than in 2014, when the weather was colder and wetter. There were also fewer arthropods, the birds’ food source, available in 2014. Longspur nestlings grew faster than sparrow nestlings both years, but sparrows were unaffected by temperature, perhaps because sparrows nest in shrubs rather than on the open tundra. Nestlings from clutches that were laid earlier did grow faster than those from later clutches, since birds that arrived on their breeding grounds early could claim the best territories for raising young.

Challenging conditions force parents to make a choice between taking care of themselves and taking care of their offspring. Climate change is likely to bring new uncertainty for birds nesting in the Arctic—while warmer temperatures will favor higher nestling growth rates, climate models also predict more frequent storms and increased precipitation.

The research was carried out on the North Slope of Alaska’s Brooks Range, where researchers tracked 110 White-crowned Sparrow nestlings and 136 Lapland Longspur nestlings over two years, representing 58 total nests. Perez had previously studied parental energy expenditure and incubation. “When I became involved in our project based out of Toolik Lake looking at effects of interannual variation across trophic levels and how that ultimately plays out in terms of reproductive success of songbirds, expanding to an examination of nestling growth rates with regards to variation in environmental conditions seemed like a logical next step,” he says.

“Species at range edges are sentinels of climate change because they often experience high environmental variability and harshness,” according to Dr. Daniel Ardia of Franklin and Marshall College, an expert on the role of environmental variation in bird behavior and physiology. “Pérez and his co-authors reveal the direct effects of weather variation on nestling growth, an important determinant of fitness, showing how climate variability might have strong negative effects of populations. What makes the study so compelling is that they were able to link weather variability to food supply showing the causal link between predicted weather variation and reproduction.”

Nestling growth rates in relation to food abundance and weather in the Arctic is available at http://www.aoucospubs.org/doi/full/10.1642/AUK-15-111.1.

About the journal: The Auk: Ornithological Advances is a peer-reviewed, international journal of ornithology that began in 1884 as the official publication of the American Ornithologists’ Union. In 2009, The Auk was honored as one of the 100 most influential journals of biology and medicine over the past 100 years.