How do birds evolve over generations? How do different bird populations diverge into new species? Ornithologists have been asking these questions since the days of Darwin, but rapid advances in genetic sequencing techniques in the last few years have brought answers more in reach than ever. A Review forthcoming in The Auk: Ornithological Advances describes some of the newest and most exciting developments in the field of “high-throughput sequencing,” a collection of techniques for studying broad regions of a genome rather than individual genes.

High-throughput sequencing has been dropping in cost and complexity; once only available to large research consortiums, these methods are now feasible for smaller labs that were previously limited to working with individual genes or with mitochondrial DNA. “It’s like going from seeing with a few light sensitive cells that can only detect the difference between night and day to a fully formed eye that can see all of the stars in the night sky,” says David Toews of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the lead author of the Review.

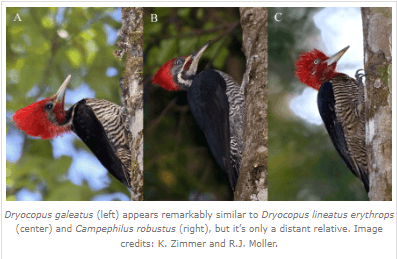

Because high-throughput sequencing data looks at many genes instead of just a few, it makes it easier to identify very subtle genetic differences between populations, such as the genetics underlying small differences in plumage patterns between different subspecies of Wilson’s Warbler. It can also provide a fresh look at the genetic changes that occur in “hybrid zones,” where the ranges of closely related species overlap and members of the species breed freely with each other, such as where Black-capped and Carolina Chickadees meet in Pennsylvania. The process of one species splitting into two, such as what may be happening with the coastal and inland subspecies of Swainson’s Thrush, is another intriguing area for study.

“Right now, genetic technology is advancing so fast that it is mind-boggling to keep up with the latest techniques, the questions that are becoming available to ask, and the answers that the data gives us,” says Jack Dumbacher of the California Academy of Sciences, an expert in bird molecular ecology who was not involved with the paper. “This is not only a review of what we are learning, but how we are learning it and what we need to be thinking about next. The paper should be a great source for students trying to figure out how to get into this complex field of modern ornithological genetics.”

“I think as the methods mature, so will the field—we are really in an exploratory stage with this data. I think once the questions and theory become more refined, we will be able to be more hypothesis-driven in the study of avian genomics,” adds Toews. “In the end, however, this is just a tool. I think the tool is a powerful one, but it is really in the application to interesting biological questions that the biggest advances will come.”

Genomic approaches to understanding population divergence and speciation in birds is available at http://www.aoucospubs.org/doi/full/10.1642/AUK-15-51.1. Contact: David Toews, toews@cornell.edu.

About the journal: The Auk: Ornithological Advances is a peer-reviewed, international journal of ornithology that began in 1884 as the official publication of the American Ornithologists’ Union. In 2009, The Auk was honored as one of the 100 most influential journals of biology and medicine over the past 100 years.